Hay and Pasture Insects

Fall armyworm

Two species of armyworms—fall armyworms and true armyworms—can damage improved pastures, temporary winter pastures, permanent pastures, and small grains. Populations of these caterpillars can increase quickly, move in large masses (or armies) to fields in search of food, and consume a crop almost overnight.

Although it attacks many other crops, the fall armyworm (Fig. 15) feeds primarily on bermudagrass, ryegrass, sorghum, and wheat. It is a major pest of permanent and improved pastures in most parts of Texas. It is most abundant in mid-summer through early November.

Fall armyworms are green, brown, or black, all having white to yellowish lines running from head to tail. A distinct white line between the eyes forms a characteristic inverted “Y” pattern on the face (Fig 16). Four black spots form a square near the back.

At first, armyworms are tiny (1/8 inch) and often go unnoticed because they cause little plant damage. The larvae feed for 2 to 3 weeks; when full grown, they are about 1 to 1½ inches long. Given their immense appetite, great numbers, and marching ability, fall armyworms can damage entire fields or pastures in 2 or 3 days.

Once the armyworm larva completes feeding, it tunnels about an inch into the soil and enters the pupal stage. The moth (Fig. 17) emerges from the pupa in about 10 days and repeats the life cycle.

The fall armyworm moth has a wingspan of about 1½ inches. The front pair of wings is dark gray with an irregular pattern of light and dark areas.

The moths are active at night, when they feed on nectar and deposit egg masses (Fig. 18). A single female can deposit up to 2,000 eggs. There are four to five generations per year.

The fall armyworm apparently does not overwinter in North Texas; it overwinters in the pupal stage in South Texas.

Populations increase in South Texas in early spring, with successive generations moving northward as the year progresses. They may infest pastures from early summer until the first frost in the fall.

Ground beetles, insect viruses, some bird species, and parasitic wasps and flies help suppress armyworm numbers. However, these natural enemies can be overwhelmed when migrating moths move into an area, and the weather conditions favor high survival of eggs and larvae.

Management

The key to managing fall armyworms is to inspect the fields often to detect infestations before they cause economic damage.

Fall armyworm outbreaks in pastures and hayfields often occur after rain, which apparently creates favorable conditions that allow many eggs and small larvae to survive. Especially susceptible to fall armyworm infestations are recently fertilized and irrigated fields that have a dense canopy and vigorous growth.

Also monitor volunteer wheat and weedy grasses in ditches and around fields, which may be a source of armyworms that can move into the nearby crop. Look for the larvae feeding on the grass in late evening and early morning and during cool, cloudy weather.

On hot days, scout for armyworms low in the grass canopy or even on the soil, where they hide under loose soil and fallen leaves. You may need to get on your hands and knees to examine the grass closely.

Another scouting tactic is to roughly run your hands through the grass in a 1- to 2-square-foot area to knock the larvae to the soil and make them easier to see. Then part the grass to look for larvae on the soil. A sweep net is also effective for sampling hayfields for fall armyworms. When the fields are wet with dew, armyworms can stick to the rubber boots of people walking through the field.

Small larvae chew the green layer from the leaves, creating a clearing or “windowpane” effect, and later feed on the leaf margins. This leaf damage can indicate the need to sample for larvae.

Once the larvae are longer than ¾ inch, they eat dramatically more foliage. During their final 2 or 3 days of feeding, armyworms consume 80 percent of the total foliage consumed during their entire development.

The action level for armyworms depends on the crop’s value and growth stage.

Seedlings can tolerate fewer armyworms than can older plants. In bermudagrass hay, consider using an insecticide if there are more than two or three armyworms ½ inch or longer per square foot.

If practical, apply the insecticide (Table 1) early in the morning or late in the evening when the larvae are most active and most likely to contact the insecticide spray. If the field is near harvest, an option is to harvest early rather than use insecticide.

True armyworm

The true armyworm is most common during the spring, when it feeds on wheat, rye grass, winter pastures, and seedling corn and sorghum.

The larvae are dark green to nearly black with longitudinal stripes (Fig. 19). The head capsule is yellow-brown with a dark, netlike pattern.

The adult is a night-flying moth (Fig. 20). The wings are pale brown to gray with a single, small white spot near the center of each forewing.

The eggs are laid in rows on the leaves, often between the leaf sheath and blade, and are difficult to find. Egg survival is favored by cool temperatures, which may explain why true armyworm numbers often decline when temperatures rise in early summer.

Like the fall armyworm, true armyworms can reach huge numbers and move en masse to fields for food. True armyworm larvae develop for about 3 to 4 weeks, depending on temperature, and mature larvae are about 1⅓ inch long.

Also like fall armyworms, the small larvae consume little forage. However, when they reach ¾ to 1 inch long, they consume about 80 percent of the total foliage consumption during their entire development. The crop can be lost within days.

The larvae feed mostly on leaves; in wheat, they can feed in the seed head and may cut the head. True armyworms do not readily feed on bermudagrass but may infest pastures that have a mix of bermudagrass, wheat, and ryegrass. In these fields, the worms feed on ryegrass and wheat first, and then bermudagrass if no other cool-season grass is available.

Management

Monitor susceptible crops for true army- worms in the spring. Infestations are often associated with cool, wet weather. The armyworms often feed at night; during the day, they stay on the soil beneath dirt clods and in leaf litter and soil cracks. Look for them in the canopy in the early morning or late evening.

As with fall armyworm, the economic threshold for true armyworm infestations depends on the crop stage and value.

Infestations of two to three armyworms per square foot may justify an insecticide application.

If practical, apply insecticides in the early morning or late evening when the larvae are most active and therefore most likely to contact the insecticide spray. Insecticides listed for fall armyworm are also effective against true armyworm (Table 1).

Table 1. Insecticides labeled for fall armyworm and true armyworm in pasture, grasses, and hay. Follow label directions.

|

Active ingredient |

Insecticide |

Pre-grazing interval (days) | Pre-harvest interval for hay (days) |

Remarks |

| beta-cyfluthrin | Baythroid | 0 | 0 | Restricted use |

| carbaryl | Sevin 4F, Carbaryl 4L | 14 | 14 | General use |

| chlorantraniliprole | Prevathon, Coragen | 0 | 0 | General use |

| chlorantraniliprole + lambda-cyhalothrin | Besiege | 0 | 7 | Restricted use |

| cyfluthrin | Tombstone | 0 | 0 | Restricted use |

| diflubenzuron | Dimilin 2L | None listed | 1 | Restricted use; apply at egg hatch and when larvae are less than ½ inch long |

| gamma-cyhalothrin | Declare | 0 | 7 | Restricted use |

| lambda-cyhalothrin | Warrior II, Karate, Lambda-cy, generics | 0 | 7 for hay,

0 for forage |

Restricted use |

| malathion | Malathion 57EC | 0 | 0 | General use |

| methoxyfenozide | Intrepid | 0 | 7 | General use |

| spinosad | Tracer, Blackhawk | Allow spray to dry | 3 | General use; target small larvae or egg hatch |

| zeta-cypermethrin | Mustang Maxx | Allow spray to dry | 0 | Restricted use |

Grasshoppers

Although grasshoppers damage Texas crops locally most years, in some years they become abundant and cause damage regionally. Weather conditions primarily determine grasshopper abundance. Out- breaks often occur after consecutive years of hot, dry summers and warm autumns.

In contrast, cool, wet weather slows the growth of grasshoppers and favors the fungal diseases that kill them. Warm, dry weather in the fall enables grasshoppers more time to feed and lay eggs. Thus, grasshoppers increase during drought conditions.

Cold does not affect grasshoppers because they overwinter as eggs in the soil.

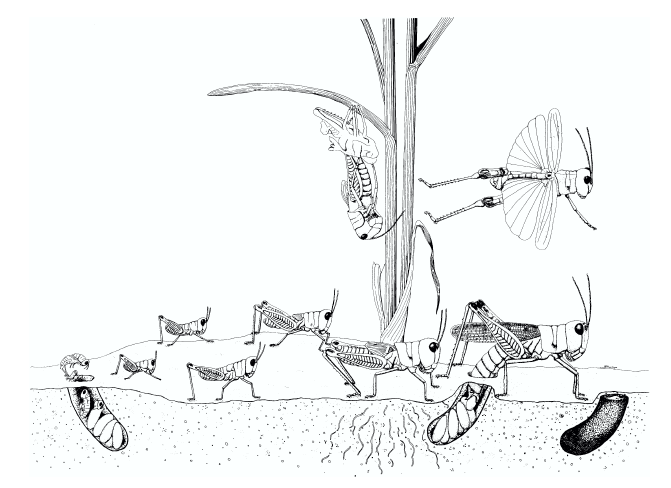

Of the 150 species of grasshoppers in Texas, only five cause most of the crop damage: the differential grasshopper, red- legged grasshopper, migratory grasshopper, two-striped grasshopper, and Packard grasshopper (Figs. 21 through 25). These species’ biology, damage, and management are similar.

In the fall, grasshoppers deposit clusters of eggs ½ to 2 inches deep in the soil. They are laid in the undisturbed soil of untilled fields, fencerows, ditches, and hayfields.

The eggs hatch in spring and early summer. Because the eggs of different grasshopper species hatch at different times, young grasshoppers can be seen through- out the spring and summer.

As the grasshoppers grow, they shed their old skin (molt) and grow a new, larger skin. The periods between molting are called instars; grasshoppers complete five or six instars before the final molt to the adult stage.

The adult stage has fully developed wings and can fly. It takes 40 to 60 days for a grasshopper to develop from egg to adult (Fig. 26); most species complete only one generation a year.

As the weeds mature and dry during the summer, grasshoppers fly in search of green plants and can concentrate in crops, orchards, and irrigated landscapes. Grasshoppers are active until late fall, when the adults begin to die or a killing frost occurs.

Management

Control weeds to remove the food needed by young grasshoppers and to discourage the adults from laying eggs in the area.

However, destroying weeds already infest- ed with many grasshoppers can force them to move to nearby crops or landscapes. Control the grasshoppers in the weedy area first with an insecticide or be ready to protect nearby crops if they become infested.

Because female grasshoppers prefer to lay eggs in undisturbed soil, tilling the soil lightly in mid- to late-summer can discourage them from laying eggs.

This insect is susceptible to many insecti- cides (Table 2). However, some persist for only a few days, allowing the grasshoppers to quickly reinvade the treated area. The period of control depends on the intensity of reinvasion and the insecticide’s active ingredient and application rate.

Table 2. Insecticides labeled for grasshoppers in pastures, grasses, and hay. Follow label directions.

|

Active ingredient |

Insecticide |

Pre-grazing interval (days) | Pre-harvest interval for hay (days) |

Remarks |

| beta-cyfluthrin | Baythroid | 0 | 0 | Restricted use |

| carbaryl | Sevin 4F, Carbaryl 4L | 14 | 14 | General use |

| chlorantraniliprole | Prevathon, Coragen | 0 | 0 | General use |

| chlorantraniliprole + lambda-cyhalothrin | Besiege | 0 | 7 | Restricted use |

| cyfluthrin | Tombstone | 0 | 0 | Restricted use |

| diflubenzuron | Dimilin 2L | None listed | 1 | Restricted use: apply at egg hatch and when immature grasshoppers are less than ½ inch long |

| gamma-cyhalothrin | Declare | 0 | 7 | Restricted use |

| lambda-cyhalothrin | Warrior II, Karate, Lambda-cy, generics | 0 | 7 for hay,

0 for forage |

Restricted use |

| malathion | Malathion | 0 | 0 | General use |

| zeta-cypermethrin | Mustang Maxx | 0 | 0 | Restricted use |

Controlling grasshoppers over a large area will reduce the number that can reinfest the crop. Monitor grasshopper infestations, and treat them while the insects are still small, before they develop wings and move into crops and landscapes. Small grasshoppers are more susceptible to insecticides, and usually a smaller area will require treatment.

To determine the size of an infestation, estimate the number of grasshoppers per square yard:

- While walking across the field, estimate the number of adult grasshoppers in an area of 1 square yard. If most of the grasshoppers are less than ½ inch long, divide the number of grasshoppers by three to get the adult equivalent.

- Walk 15 to 20 paces and again estimate the number in one square

- Repeat these estimates for at least 18 square

- Calculate the average number of adults per square

The economic threshold is generally an average of 21 or more adult grasshoppers per square yard along the field margin, or eight or more per square yard in the field. When deciding whether to treat, factor in the crop stage and value as well as the grasshopper feeding damage.

Figure 26. Grasshopper life cycle. Field Guide to Common Western Grasshoppers 3rd edition. By the Wyoming Agricultural Experiment Station

Bermudagrass stem maggot

The bermudagrass stem maggot is a new pest of bermudagrass forage in Texas and the United States. It infests only bermudagrass and stargrass.

Native to South Asia, this stem maggot was first reported in Georgia in 2010. In Texas, it was first found in 2013 in East and South Texas. Since then, it has been reported near San Antonio, Lubbock, and El Paso and is believed to be distributed throughout the state.

The adult stage is a small, yellow fly (Fig. 27) that lays its eggs on the bermudagrass plant. Once the egg hatches, the larva, or maggot, moves to the top node of the stem, burrows into the shoot, and consumes the plant material in the stem. This stem damage results in the death of the top two or three leaves while the rest of the plant remains green.

Fields infested with this pest appear to have frost damage. Cutting open the stem below these dead leaves will reveal the tun- nel created by the maggot and possibly the maggot itself. Full-grown, the maggot is yellowish and about 1/8 inch long (Fig. 28).

The maggots are difficult to find because they often complete feeding and leave the stem before the upper leaves turn brown or white and die. Once feeding is complete, the maggot drops to the ground and enters the pupal stage.

The adult fly later emerges from the pupa. The life cycle from egg to adult fly requires about 2 to 3 weeks, and there are several generations a year.

The feeding halts shoot elongation, stunts plant growth, and delays the accumulation of dry matter (Fig. 29). In response, the plant will grow another shoot, which the bermudagrass stem maggot can also attack, further stunting and delaying regrowth.

Damage is more common in fine-stemmed cultivars such as Coastal, Alicia, Russell, and common bermudagrass. Infestations in coarse-stemmed varieties such as Tifton 85 are less common yet can be significant, especially late in the season.

The stem maggot is usually not a pest of grazed pastures because livestock consume the eggs and maggot with the grass, preventing an increase in the fly population.

Management

Research results in Georgia and Alabama suggest that if you find significant dam- age, you should harvest the crop as soon as weather allows. Maggots feeding in the stem will die once the crop is cut and dried for harvest.

However, flies will emerge from the pupae already in the soil and reinfest the field.

To protect the regrowth from infestation, apply a labeled insecticide (Table 3) about 7 to 10 days after cutting.

This insecticide treatment will kill the adults but not the larvae already feeding in the stems. If the infestation is extensive, consider a second application 5 to 7 days later.

Unknown so far are effective methods for sampling BSM flies or larvae and guidelines for determining when an insecticide treatment is needed.

Once a field is cut, the maggots that are feeding in the stems die as the grass dries. For this reason, bermudagrass maggots are unlikely to be transported in hay. The adult is a strong flier; this is the stage when the pest moves to new fields.

White grubs and May, June, and green June beetles

Figure 30. White grub. Photo by Casey Reynolds, Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service

The larval stages of May, June, and green June beetles are called white grubs (Fig. 30). The larvae are characteristically “C-shaped,” with white bodies and tan to brown heads. Their size varies according to age and species. The last abdominal segment is transparent, and the digested material inside the larva is visible.

May and June beetles (Fig. 31) are large, brown, and attracted to outdoor lights at night in spring and early summer. May and June beetles deposit eggs in the soil during the spring and summer.

The grubs feed during the summer and fall and then overwinter. They damage plants by feeding on the roots, which kills the plants, thins stands, and allows weeds to invade the bare soil.

Figure 31. May/June beetle adult

Some species have a 1-year life cycle and emerge as adults the next spring. Other species remain as grubs for a second sum- mer and develop as adults the following spring; they require 2 years to complete a generation.

Green June beetle grubs are very large—up to 2 inches long—and crawl on their backs. The adult beetle (Fig. 32) is velvety green and ½ to 1 inch long. Females deposit eggs in sandy and sandy loam soils, especially in fields high in organic matter, such as pastures where broiler litter, manure, or other organic matter has been applied.

Although green June beetle grubs feed primarily on organic matter, they occasionally chew on tender grass roots. Most of their damage in pastures and hay results from tunneling near the soil surface which results in the death of grass due to uprooting

Figure 32. Green June beetle adult. Photo by Judy Gallagher (CC BY 2.0)

and desiccation. The green June beetle adult feeds on ripening fruit and can be serious pests of grapes and peaches just before harvest.

Management

No insecticides are labeled to control the white grubs of May or June beetles in pas- tures and hay. The green June beetle grub comes to the surface of the soil at night to feed, and insecticides, such as carbaryl, applied to the soil surface can effectively control this pest.

For more information on controlling green June beetles, see Biology and Control of Green June Beetles, by the Alabama Extension Service, at http://www.aces.edu/pubs/ docs/A/ANR-0991/index2.tmpl.

Red imported fire ant

Although red imported fire ants do not feed on grasses, their damage can still warrant management:

- The ants threaten livestock, especially newborn

- Custom cutting and baling operators may charge more for their services where fire ant infestations are severe, and field workers can be stung when handling square

- Because fire ants can infest hay and be transported to uninfested areas, hay shipped out of quarantined areas must be certified as free of fire ants by Texas Department of

Under Texas Administrative Code, Title 4, Chapter 19, Subchapter J, hay from counties infested by red imported fire ants is prohibited from being moved into non-infested counties. An exception is if the hay has been stored on a concrete slab

or heavy duty plastic and the site where it was stored has been kept free of red imported fire ants using appropriate bait treatments.

Before moving hay from an infested county to a non-infested county in Texas or to another state, the hay producer or shipper must contact the local Texas Department of Agriculture office to have the hay inspected and to receive a phytosanitary certificate.

Management

The most cost-effective method of controlling fire ants over a large area is to broadcast a bait-formulated product (Table 4) rather than treating individu- al mounds. These baits are commonly

applied at a rate of 1 to 1½ pounds per acre using a held-held applicator or a seeder attached to a truck or ATV and calibrated to apply fire ant bait. Baits can also be applied by airplane.

The bait should be fresh and applied when the ants are actively foraging in late spring, summer, or early fall.

Table 4. Insecticide baits labeled for control of red imported fire ants in grazed pastures and hay. Follow label directions.

| hydramethylnon | Amdro Pro | 0 | 7 | Maximum control observed in about 3–6 weeks. General use insecticide |

| methoprene | Extinguish | 0 | 0 | Control achieved in about 1–3 months if applied in the spring and 3-6 months if applied in the fall. One application per year is usually sufficient for good suppression. General use insecticide |

| methoprene + hydramethylnon | Extinguish Plus | 0 | 7 | Combines rapid control of Amdro Pro and the longer residual control of Extinguish. General use insecticide |

| pyriproxyfen | Esteem | 0 | 1 | Labeled for use in hay pastures or with livestock usedfor food or feed production. Control is relatively slow,1–3 months applied in spring, 3–6 months in fall. General use insecticide |

Southern and tawny mole crickets

Two species, the southern and tawny mole crickets, are pests of improved pastures of bermudagrass and bahiagrass, turf grass, and other crops in Texas.

Mole crickets are brown, cylindrical insects with large, shovel-like front legs modified for digging in the soil. The adults are about 1½ inches long, can run quickly, and fly at night.

Mole crickets deposit eggs in the soil in April and May; the nymphs develop during the summer; and some nymphs mature into adults in the fall. Nymphs and adults overwinter, and there is usually one generation per year.

The southern mole cricket (Fig. 33) is widely distributed east of I-35 from Dallas to Corpus Christi. It tunnels at night just below the soil surface, where it feeds on insects and earthworms.

Tunneling loosens the soil around plant roots, causing the root to dry out and the plants to die. Tunnels dug by the adults are conspicuous on the soil surface; those created by immature mole crickets may be difficult to detect.

The tawny mole cricket was first found in Texas in the Houston area and is expected to expand its range. Unlike the southern mole cricket, the tawny mole cricket feeds on living roots and plants. This feeding, along with tunneling, can cause extensive stand loss.

Both species prefer sandy soil but can also be pests in heavy clay. Crop damage is usually most severe in late summer and fall when the crickets are large and more active.

Management

No insecticides are labeled to control mole crickets in forage crops. However, to deter- mine whether mole crickets and not other insects are responsible for the crop injury:

- Dissolve 2 tablespoons of liquid dishwashing detergent in 2 gallons of

- Pour the soap solution over an area of about 4 square feet. The solution will drive the crickets to the

- Observe the area for 4 to 5 minutes and count the number of mole crick- ets that

As a point of reference, insecticide treat- ment is considered in turfgrass if two to four mole crickets come to the soil surface within 3 minutes after applying the soap solution.

Desert termites

Figure 34. Desert termite adult. Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service

Desert termites (Fig. 34) are found in bermudagrass pasture, rangeland, and bunchgrass areas in South and West Texas. They feed primarily on forbs (flowering plants other than grasses), livestock manure, and live and dead grasses.

Signs of their presence include the tubes or sheets of carton (Fig. 35) that they build around the grass stems and plants on which they feed. The carton consists of moist soil particles and termite feces glued together with saliva. The tubes protect the insects from dehydration and predators. Although rain destroys the tubes, the ter- mites quickly rebuild them.

Like earthworms in wetter environments, desert termites help water filter through the soil and break down plant material into nutrients that are available to plants. But during dry periods, the termites can denude patches of grass cover and, in some cases, promote soil erosion. In prolonged droughts, the loss of soil surface cover to feeding by desert termites may impair rainfall infiltration and increase runoff and erosion.

Their carton tubes are more visible in overgrazed pastures or during drought when the plants are less dense, which makes the area appear to have more termites.

Management

Little research has been conducted to determine the economic feasibility of con- trolling desert termites to reduce the loss of forage production. Also, no insecticides are labeled for desert termite control.

To minimize harm by desert termites, adopt practices that enhance rainfall infiltration and restore rangeland productivity, including ripping, pitting, contour furrowing, managing grazing properly, and controlling weeds and woody plants. For more information, see Texas AgriLife Extension publication E-258, Desert Termites, which is available from the county Texas A&M AgriLife Extension office or online at agrilifelearn.tamu.edu.

Figure 36. Field skipper adult. Photo by by Suzanne Cadwell

Field skipper

Although the field skipper is a rare pest of bermudagrass hayfields in northeastern Texas, populations of this insect can break out suddenly and damage bermudagrass over a wide area.

The field skipper butterfly, so named for its direct, very rapid, and often short flights, is orange-brown and has a 1-inch wingspan (Fig. 36).

The larvae are dark olive-green and have a black head (Fig. 37). The body is constricted just behind the neck, making the head appear very large. The body is smooth, tapered to the front and back, and lacks hairs or spines. Full-grown caterpillars have two or three chalky white spots on the underside between the back legs.

Figure 37. Field skipper larva. Photo by Charles T. Bryson, USDA Agricultural Research Service, Bugwood. org

The caterpillars consume the leaves of bermudagrass and St. Augustine grass, leaving only the stems. The caterpillars feed in the silken shelters they create by tying grass stems together about midway up the plants. Once they consume the grass, they may crawl in large masses across roads and damage nearby fields or lawns.

Infestations are often first detected when masses of caterpillars crawl up buildings and attack lawns around homes. As with other caterpillars, most of the feeding occurs during the final larval stages, which can quickly defoliate hayfields and lawns as they reach maturity.

Outbreaks have occurred in Texas in late June and July in 1985 and 1989. Although these insects are present every year, the conditions that lead to outbreaks are unknown.

Management

Scout bermudagrass hayfields and meadows for skipper caterpillars from late June through July. Look for bunches of grass stems tied together by silk shelters, in which the larvae feed.

Although harvesting infested fields early will reduce hay loss, many caterpillars may survive after harvest and feed on the re- growth. Insecticide may be needed if early cutting is not an option or if cut fields do not green up normally and caterpillars are alive in the field.