Dectes Stem Borer, Dectes texanus texanus

The dectes stem borer is a pest in the High Plains region. Adults are called long-horned beetles because their antennae are longer than their bodies. However, the larvae damage soybeans.

Dectes stem borer adults (Fig. 22) lay eggs in leaf petioles. After hatching, larvae tunnel down the petiole into the main stem where they bore up and down. Eventually, they girdle the inside of the stem base, causing lodging and yield loss late in the season.

Full-grown larvae are about ½ to 5/8 inch long, grub-like, and legless; their abdominal segments resemble an accordion.

Plowing or disking soybean stubble reduces populations of over- wintering adults. No-till or stale seedbed planting can result in more borers surviving the winter and creating more damage the following year. Chemical control is not recommended, but fall tillage can reduce overwintering populations.

Good weed control in and around fields can reduce alternate weed hosts. Since adults are weak fliers, infestations are often localized.

Crop rotation can help in areas where soybean production is limited.

The most effective cultural management method is to harvest as soon as possible to reduce losses caused by lodging. Scouting fields late in the season for stem borer damage helps identify problem fields that should be harvested as early as possible.

Foliage-Feeding Caterpillars

Larvae of soybean loopers, cabbage loopers, velvetbean caterpil- lars, and green cloverworms can severely defoliate soybeans, partic- ularly in the eastern half of the state. All of these caterpillars feed on leaves, and infestations usually occur during mid-to-late season.

Generally, looper larvae are the first to appear (before velvet- bean caterpillars and green cloverworms) about the time soybeans switch from vegetative to reproductive growth stages. All four species continue to build up larval populations during soybean reproductive stages.

The podfill stage is especially vulnerable. Research shows that soybeans can tolerate no more than 20 percent defoliation without substantial yield loss. Use the defoliation template to estimate the percent of leaf loss (Fig. 20):

- Compare leaflets from the top, middle, and bottom of plants to the template.

- Average the percentages of leaf loss in the field.

- Be sure to sample from all areas of the field.

- Combine the leaf loss by all four species to arrive at an overall estimate.

These leaf feeders infest fields in late summer when temperatures and humidity are high. Damage can progress rapidly; frequent scouting is crucial for timely control (Fig. 23).

Occasionally, the fungus, Noumeria rileyi, will infect larvae late in the season, killing many of them. Infected larvae turn white and hang from the foliage. Unfortunately, these disease outbreaks usually occur when larval populations are very high following substantial crop injury.

Velvetbean Caterpillar, Anticarsia gemmatalis

Large numbers of velvetbean caterpillar moths migrate into Texas each year from Central and South America. The adult moth is fairly large and usually has a diagonal black line across the wings. It deposits light green eggs singly or in groups of two to three on soybean leaves, pods, and stems. Larvae progress through six instars or stages, grow- ing larger with each molt. The older instars are much larger than the younger ones and cause the most damage.

Easily identified by their vigorous wiggling and twisting when disturbed, velvetbean caterpillars are pale yellow-green to brown and black with white or yellow stripes running lengthwise along the body (Fig. 24). They have four pairs of abdominal prolegs, plus one pair at the end of the abdomen.

Velvetbean caterpillars can produce multiple generations during the growing season, with each generation being larger than the previous one. Although velvetbean caterpillars are relatively easy to control with insecticides, undetected and uncontrolled infestations can rapidly increase to cause extensive leaf loss.

In the eastern half of Texas, populations peak late in the summer and early fall, and adults fly through the soybean canopy when disturbed.

Green Cloverworm, Hypena scabra

Like the velvetbean caterpillar, these leaf-feeding pests are more prevalent in the eastern half of the state. Green cloverworm adults (moths) hold their wings in a triangular shape when at rest and are darker than velvetbean caterpillar moths. They lay single eggs on the underside of leaves. The eggs are translucent green and turn brownish with red specks just before hatching.

Larvae, the damaging stages, are pale green with two white stripes along the sides of the body (Fig. 25). These caterpillars have three pairs of prolegs on the abdomen and one pair of prolegs at the end of the body. (Other common caterpillar species in soybeans have two or four pairs of prolegs on the abdomen.) They progress through six to seven instars. Like velvetbean caterpillars, green cloverworm larvae also wiggle vigorously when disturbed.

Green cloverworms overwinter along the Gulf where they feed on host plants year-round. Multiple generations develop each year, with later generations responsible for the most severe soybean damage.

Green cloverworms and velvetbean caterpillars are relatively easy to control with a wide array of insecticides.

Soybean Looper, Chrysodeixis includens and Cabbage Looper, Trichoplusia ni

Both soybean loopers (Fig. 26) and cabbage loopers (Fig. 27) are most common in the eastern half of the state. Usually, the cabbage looper is less abundant in soybeans than the soybean looper. The soybean looper has developed resistance to certain insecticides and can be more difficult to control than the cabbage looper. It is import- ant to distinguish cabbage loopers from soybean loopers so that if soybean loopers are plentiful, you can apply an effective insecticide.

The larvae of both species are similar; they have two pairs of abdominal prolegs and one pair of anal prolegs. The number and spacing of these prolegs causes the larvae to loop (hump their bodies) while walking, and they often remain in this looped position when stationary.

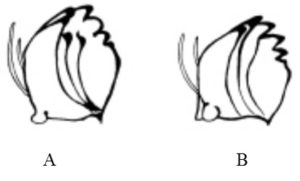

The best way to distinguish between the two species is to use a hand lens to inspect the inside surface of the mandibles. The cabbage looper has ridges that extend from the base to the edge of the mandibles. The ridges on the soybean looper mandible do not reach the edge (Fig. 28). Older larvae have larger mandibles that are easier to inspect for these characteristics.

The larval stages have six instars, with the older, larger larvae consuming the most leaf tissue. In the eastern half of the state, loopers can produce multiple generations in a growing season.

Generally, loopers begin infesting soybeans earlier than the other foliage-feeding caterpillars do. Soybean looper larvae are distributed throughout the soybean canopy but, unlike velvetbean caterpillars and green cloverworms, more are found in the lower canopy.

Both species lay single eggs on the underside of leaves. Soybean looper pupae are creamy white to green and enclosed in a silken cocoon attached to the underside of leaves. Cabbage looper pupae are brown and found on the soil surface.

Fall Armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda

Because fall armyworm caterpillars do not usually feed on soybeans, they are not a serious soybean pest in Texas. However, large numbers of fall armyworms do feed on soybean flowers in fields with prior bermu- dagrass infestations. Fall armyworms develop on the bermudagrass and, after the fields are sprayed with glyphosate, the fall armyworm larvae move from the dead bermudagrass to the flowering soybeans. In this situation, poor weed control can result in insect damage.

Because fall armyworm caterpillars do not usually feed on soybeans, they are not a serious soybean pest in Texas. However, large numbers of fall armyworms do feed on soybean flowers in fields with prior bermu- dagrass infestations. Fall armyworms develop on the bermudagrass and, after the fields are sprayed with glyphosate, the fall armyworm larvae move from the dead bermudagrass to the flowering soybeans. In this situation, poor weed control can result in insect damage.

The fall armyworm has four life stages: egg, larva, pupa, and adult. It overwinters in the pupal stage in the southern regions of Texas. Up to seven generations occur each year; the typical life cycle from egg to adult is about 28 days.

Larvae are smooth-skinned and vary from light tan or green to nearly black. Usually, larvae complete six larval instars before pupa- tion. Full-grown larvae are about 1 to 11/2 inches long, with three yellow-white hairlines down their backs (Fig. 29). On each side of the body and next to the yellow lines is a wider dark stripe. Next to that is an equally wide, wavy, yellow stripe, splotched with red. To differentiate fall armyworm larvae from other armyworm species or corn earworms, look at the head. The fall armyworm head has a conspic- uous white, inverted Y-shaped suture (seam or furrow) between the eyes.

Management and Treatment Thresholds for Foliage-Feeding Insects in Soybeans

All of these leaf-feeding caterpillars infest soybeans about the same time in late summer. Typically, populations build up to damaging levels quickly, so regular and frequent sampling from R1 through R6 is imperative.

In commercial fields, the progression from minor to virtually 100 percent leaf loss can occur in a week or less. Apply an effective insec- ticide when larvae are in the field and before defoliation exceeds 40 percent before first bloom, before 20 percent leaf damage during blooming to podfill (R1-6), and before 35 percent leaf damage after that. In most cases, uncontrolled populations of defoliating larvae will continue to increase to damaging levels (Table 2).

Many farmers in the southeastern US have adopted the Early Soybean Produc- tion System (ESPS), which involves planting an early MG soybean variety in April or earlier to avoid droughty condi- tions during pod formation and fill.

The ESPS also avoids damaging populations of defoliating caterpillars. By the time these caterpillars reach damaging levels, ESPS soybeans are close to harvest and less vulnerable to attack. Research has identified soybean varieties that are resistant or tolerant to defoliation. The Crockett variety (late MG) has a degree of resistance or non-preference, but is not widely planted due to relatively low yields and potential for lodging.