Pecan nut casebearer

Damage: The most damaging pest of pecans is the pecan nut casebearer. It infests all pecan-growing areas of Texas.

The larva feeds directly on the developing nut in the spring, soon after pollination in April (South Texas) through early June (North Texas). This spring generation is the most damaging, as a single larva often destroys all the nutlets in a cluster (Fig. 4).

Biology: The adult casebearer is a gray moth about ⅓ inch long (Fig. 5). The moths deposit eggs on pecan nuts at night. Before hatching, the greenish-white to white eggs change to pink or red. The eggs hatch in 4 to 5 days, and the empty white eggshell remains on the nut.

After feeding for a day or two on a nearby bud below the nut cluster, the tiny larvae tunnel into the pecan nut. They often leave visible silk and black excrement (frass) (Fig. 4) on the outsides of infested nuts. The larvae feed inside the pecan nuts for 3 to 4 weeks.

The larvae are olive gray and reach about ½ inch long (Fig. 5). Full-grown larvae pupate in the pecan nut; adult moths emerge about 9 to 14 days later.

Control: Apply a labeled insecticide as the eggs begin to hatch (Table 1, page 18). Look for eggs on the nutlets in the spring just after pollination when tiny nuts are forming. Flag egg-infested nut clusters to monitor egg hatch.

Insecticides containing spinosad are effective, leave a residue that remains effective for some time (have some residual effect), and harm beneficial insects less than do other insecticides.

To maximize the insecticide’s residual activity, delay treatment until you see the first egg hatch. Once inside the nuts, the larvae are protected from insecticides.

Hickory Shuckworm

Damage: Shuckworm larvae tunnel in the shuck, interrupting the flow of nutrients and water needed for the kernels to develop normally. Infested nuts are scarred, mature more slowly, and are usually of poor quality (Fig. 6).

Damaged shucks stick to the nuts and fail to open, creating sticktights. Infestations before shell hardening may cause the nuts to fall.

Biology: Adult shuckworms are dark-brown to grayish-black moths about ⅜ inch long. Female moths attach single eggs to the shuck using a creamy white substance that is visible on the shuck surface.

The tiny larva hatches in a few days and burrows into the shuck to feed for about 15 to 20 days. Mature larvae are about ½ inch long and cream colored with light-brown heads (Fig. 7). They pupate in the shuck, and the moth soon emerges.

Shuckworms overwinter as full-grown larvae in old pecan shucks on the tree or the orchard floor. Several generations are completed each

year.

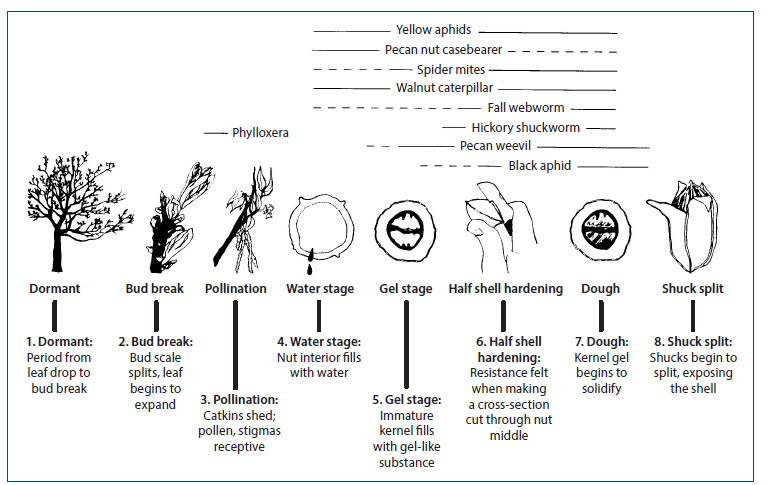

Control: Pecans are most susceptible to hickory shuckworm damage during the water through gel stages (Fig. 30, page 19).

If the orchard has a history of shuckworm damage, apply an insecticide such as spinosad when pecans reach the half-shell hardening stage. You may need to spray again 10 to 14 days later.

To reduce shuckworm infestations, remove and destroy old shucks and dropped nuts, where the shuckworms overwinter.

Stinkbugs and leaffooted bugs

Damage: Brown and green stinkbugs and leaffooted bugs have piercing-sucking mouthparts and penetrate the shuck to feed on the developing kernel.

Nuts injured before the shells harden fall from the tree. Feed- ing after shell hardening causes brown or black spots on the ker- nel (Fig. 8). The affected areas taste bitter.

Biology: These bugs overwinter as adults (Fig. 9) under fallen leaves and in other sheltered places on the ground. Populations increase in the summer, when the adults lay eggs on many crops and weeds.

Fields of soybeans, other legumes, and sorghum may be sources of adults that fly to pecans in late summer and fall. Infes- tations are usually largest from September through shuck split.

Control: Stinkbugs and leaffooted bugs are difficult to control with insecticides, especially those labeled for use in backyard orchards.

Figure 9. Brown stinkbug (from left) , Bill Ree, AgriLife Extension, green stinkbug, Bill Ree, AgriLife Extension, and leaffooted bug.

Pecan weevil

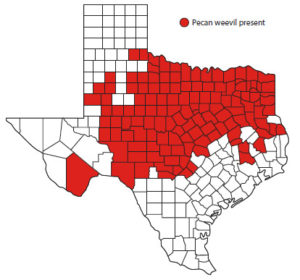

Damage: The pecan weevil is found throughout most of Texas (Fig. 10). Where present, this weevil is the most damaging late-season pecan pest.

Adult weevils feed on pecans in August and September, causing nut drop. However, this loss is usually insignificant.

A much greater loss results from pecan weevil grubs feeding on developing kernels in September, October, and November. Once the grubs have com- pleted feeding, they exit the pecan, leaving a neatly drilled hole (Fig. 11), which is evidence of weevil feeding. However, before the grubs exit, there is no obvious external evidence that a whole pecan contains developing weevil grubs. When the nut is later cracked, the damaged kernel is visible. Some pecan weevil larvae may still be inside the nut at cracking time.

Biology: Adult weevils (Fig. 11) emerge from the soil from mid-August through early September or later if delayed by drought. The adults feed on nuts and live for several weeks.

Once the nuts reach the gel stage (Fig. 30), they are suitable for egg laying . For this reason, early-maturing varieties are often infested first.

The female weevil drills a hole through the shell and deposits three or four eggs within the developing kernel. The larvae hatch from the eggs and feed inside the nut, destroying the kernel (Fig. 11).

The larvae emerge from the nuts about 42 days after the eggs are deposited. Larvae chew a clean, round, BB-sized hole in the shell—easily identified as pecan weevil damage (Fig. 11). Finding pecans on the ground with these characteristic holes is evidence that pecan weevils are in the orchard.

Full-grown larvae emerge from the nuts in late September and continue until as late as December. Emerged larvae fall to the ground, burrow 4 to 12 inches into the soil, and build cells, where they remain for 8 to 10 months. Most of the larvae then pupate and transform to the adult stage within a few weeks.

The adults remain in the underground cells for a second year before emerging from the soil the following summer. This is a 2-year life cycle.

Figure 11. Pecan weevil adult (from left) (Clemson University – USDA Cooperative Extension Slide Series, Bugwood.org), holes drilled by the full grown larvae to exit the pecan, and grubs and damage (Bill Ree, Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service)

About 10 percent of the larvae do not pupate after the first year but remain as larvae for 2 years. They emerge from the soil as adults the third year (3-year life cycle).

Control: Apply an insecticide spray to the foliage to kill the adults before they deposit eggs into pecans. Spraying large pecan trees may not be practical in a home orchard.

Applying an insecticide or sticky barrier to the trunk of pecan trees can sometimes help control pecan weevil. As the adults emerge from the soil, they crawl or fly to the trunk and crawl up it into the canopy, where they infest the nuts.

Spraying the pecan trunk with an insecticide (bifenthrin) leaves a residue that can kill pecan weevils climbing up the trunk. Spray the insecticide on the trunk from the ground level to about 8 feet above the ground, and reapply it weekly during weevil emergence.

A sticky band of Tree Tanglefoot Insect Barrier applied around the tree trunk can also capture weevils crawling up the trunk and prevent some from reaching the canopy. Place the barrier about 5 to 6 feet above the ground and reapply the barrier as dust and leaves stick to the band.

Because pecan weevils from untreated trees can fly directly from tree to tree, trunk barriers using an insecticide or Tree Tanglefoot may not be effective under these conditions.

Research is under way to evaluate nematodes and other biopesticides to control pecan weevils. The current biopesticides proven effective by research are expensive, up to $80 per tree.

For the most effective control, spray insecticide into the tree canopy to kill the adults before they deposit eggs inside pecans. Bifenthrin is labeled for pecan weevil control (Table 1).

Make the first application when the nuts reach the gel to early dough stage and adult weevils are present. The timing of gel stage/early dough formation varies by cultivar maturity and can range from early to late August. To monitor kernel development, cut pecans and check for gel and dough formation (Fig. 30).

A second application, 7 to 10 days after the first, is usually necessary unless drought has delayed weevil emergence from the soil. A good watering under the tree canopy will help reduce drought-delayed emergence of adults.

If weevils emerge late, continue to monitor emergence and reapply the insecticide at 7- to 10-day intervals as the weevils continue to emerge.

For information on how to monitor pecan weevil emergence, see the Texas A&M AgriLife publication Managing Insect and Mite Pests of Commercial Pecans, available online at http:// agrilifelearn.tamu.edu. Watch for aphid infestations, which may increase after you apply insecticide for pecan weevil control.

Do not transport nuts infested with pecan weevils to wee vil-free areas, as they can be the source of a new infestation. Also, destroy infested nuts after harvest.

Harvesting early, before weevil grubs have exited the nuts, physically removes the grubs from the orchard and can reduce weevil infestations if done every year.